Think It’s a Brick Building? The 1884 Sanborn Map Says “Think Again”

Above: The circa-1884 First National Bank building on the corner of Center and Main Streets in Richfield Springs, New York, will begin a new life this year as THE BANK LOFTS—a mixed-use residential building retrofit to Phius standards. Image: Courtesy of Richfield Springs Historical Association & Museum.

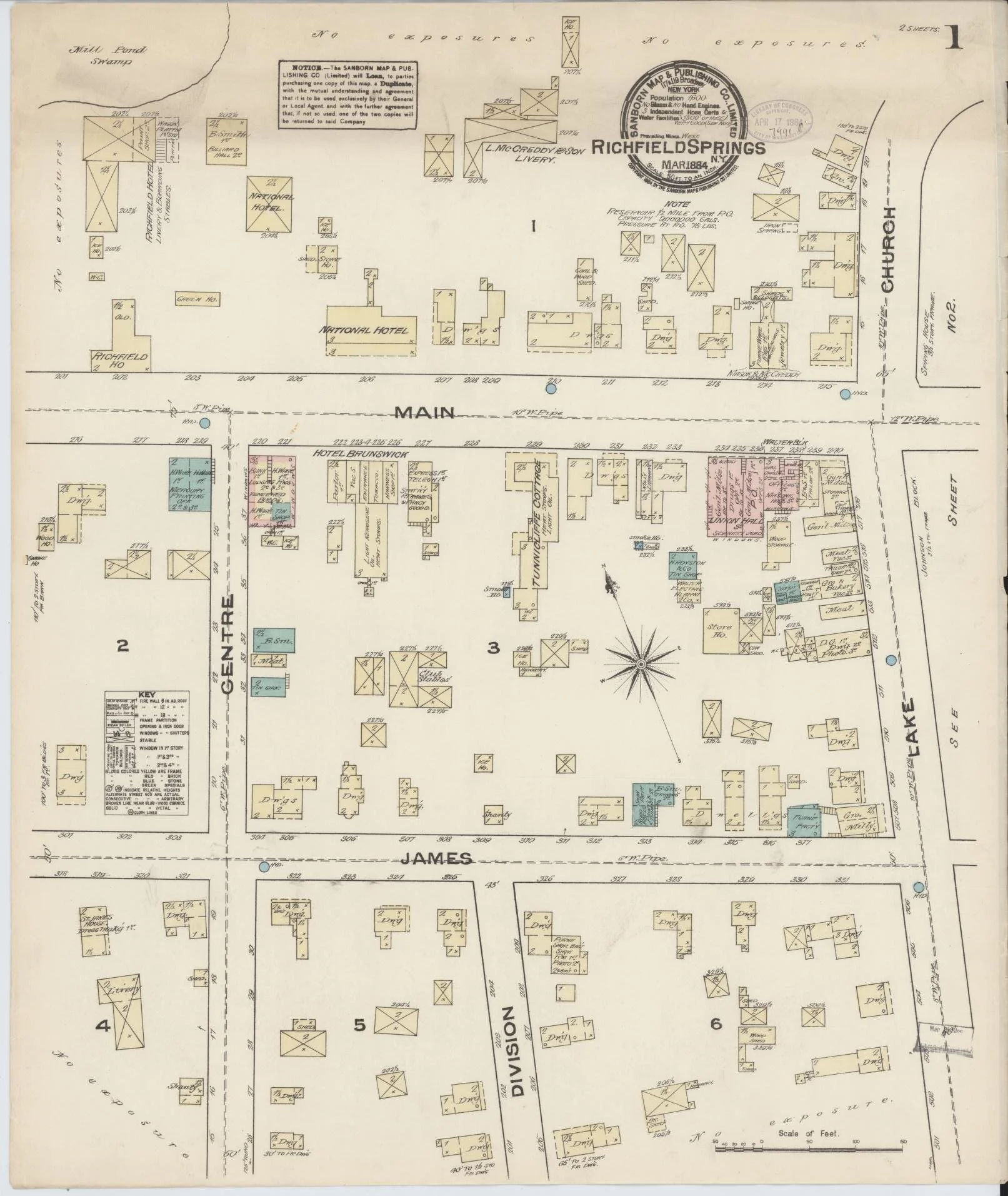

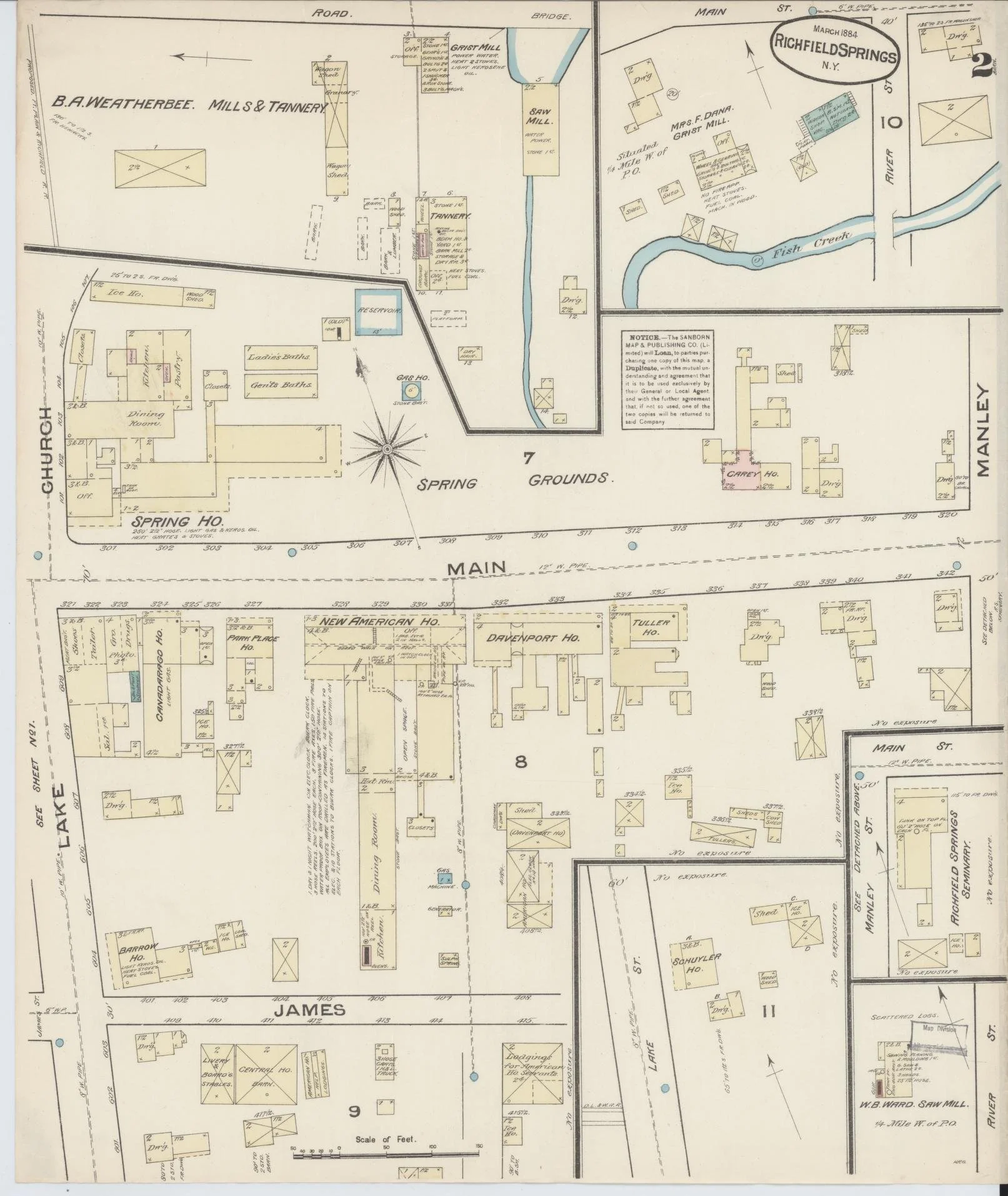

Above: The Sanborn fire insurance map published in March 1884 provides a fascinating flashback into what life was like in the village of Richfield Springs, New York, when THE BANK LOFTS building was brand new. All map images this page: Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Sanborn Maps Collection.

Reading an old Sanborn fire insurance map is like delving into a historical figure’s secret diary. What was the object of our curiosity really like when they were young? How did they reflect their times and the culture of their community? How did life change them?

We will never know all the secrets stored in the memory vault of THE BANK LOFTS’ 140-year-old building, but the Sanborn Map & Publishing Co.’s March 1884 inventory of Richfield Springs, NY (entered into the Library of Congress on April 17th of that year) shares a glimpse into the life of the former First National Bank building when it was brand new.

STRUCTURALLY, IT WAS A BIT OF AN OUTLIER

Built on the corner of Center and Main in the heart of the village business district, the 1880s building looks like a classic red-brick commercial block building from the street.

But the three-and-a-half-story structure is not solid masonry. It is "brick veneered" on all four sides (as indicated by the diagram's reddish watercolor outline) over a wood-frame structure (coded yellow on the map).

It is the only such structure on the map.

Above: The March 1884 Sanborn map of Richfield Springs, NY, depicts the then-new First National Bank building as a rectangle outlined in reddish pink with a yellow and green center.

Below: The Sanborn Map & Publishing Co. used color-coding to indicate a structure’s primary building materials. For example: Brick buildings were solid reddish pink, with the number of stories written in by hand (in the case of the bank building 3 1/2 stories). Wood-frame buildings were colored solid yellow. Yellow buildings outlined in reddish pink indicated a wood framed structure veneered in brick. On the 1884 map of Richfield Springs, the bank building is the only one of its kind.

If you didn’t know better, you might never guess there’s a barnlike wood-frame skeleton hidden beneath the building’s formal wood-trimmed, brick façade.

UP ON THE ROOF

The hollow circle ( o ) placed in the bank building diagram’s upper-right corner (shown in image above) reveals that, in the beginning, the structure had a “noncombustible roof covering of metal, slate, tile, or asbestos shingles,” very likely tin in this case.

In the late-19th-century, tin would have been a relatively low-cost roofing material when compared to other period options like copper or slate shingles.

The durability and cost of the materials would have been more important considerations to the bank building owners than looks alone in this instance: After all, the 44-foot structure’s flat roof would remain hidden from view behind the building’s decorative cornice.

Although properly maintained metal roofs have been known to last 80 to 100 years or more, this one was long gone when our team arrived, replaced by a leaky patchwork. Complete roof replacement, including new underlayment, was one of our top tasks (no pun intended) when we began the construction phase of our project late last winter.

Fire resistive materials like red bricks and metal were practical choices for a building that traded in paper money. But they were also symbolic ones, sending a message that “your money is safe here.”

In a future post, we’ll share more on how structural nuances factored into our approach to retrofitting the old bank building to safe, clean, resilient Phius standards.

Above: Page 1 of the Sanborn map of Richfield Springs dated March 1884 shows our brick-veneered building on the east corner of Centre (as it was then often spelled) and Main Streets in the heart of the village’s historic downtown commercial corridor.

Below: A key to some of the cartographer’s cryptic markings.

THE BANK LOFTS carbon-neutral adaptive reuse design transforms the 140-year-old building’s two upper stories into beautiful, light-filled, long-term rental apartments.

UPSTAIRS, DOWNSTAIRS

Even when brand new in 1884, the building many residents of Richfield Springs still refer to as “the bank ” was mixed use.

Wood-frame partitions (indicated by - - - - - lines) divided the first-floor commercial space into multiple functions:

Banking offices were housed on the west side of the first floor.

A hardware store occupied the eastern storefront.

A tin shop (colored green to note the space’s “special” fire resilience, necessitated by its function) was tucked in the rear half .

The building’s resort-era owners rented the second and third floors as Lodging Rooms, which they advertised to attract seasonal boarders. The light-filled, high-ceilinged upper stories will soon house THE BANK LOFTS’ long-term rental apartments.

Out back, an open walkway once led from the rear of the main building to a small, single-story wood-frame structure with a shingled roof (indicated by the X), which contained a W.C. (aka outhouse) on one side and an icehouse on the other—reminding us that private baths and modern, all-electric kitchens are beautiful things.

Page 2 of the March 1884 Sanborn map of Richfield Springs.

A TURNING POINT

The vast majority of buildings in the Village of Richfield Springs were constructed of wood. Many of the ones depicted on the March 1884 Sanborn map have vanished over time. Some were destroyed by fire. Others were victims of neglect or fell to ruin in a struggling post-industrial Main Street economy that deemed formerly thriving summer spa towns like Richfield Springs out of fashion and obsolete.

The 1884 First National Bank building survives, but by the 21st century, decades of deferred maintenance and systems updates had left the beloved local landmark vacant and dangerously out of code. It, too, was at risk of becoming just a memory preserved on a map and in the photo archives of the Richfield Springs Historical Association & Museum.

THE BANK LOFTS team is on a mission to help get Richfield Springs back on the map of great small towns to live, work, and play in.

Thanks to the community-minded vision of THE BANK LOFTS owners Faith E. Gay and Francesca Zambello; the commitment of our team at River Architects, PLLC, and Simple Integrity, LLC; and with the generous support of NYSERDA, we are well on our way to meeting our ambitious goal of creating a clean, healthy, and comfortable live/work/play environment for a new generation.

Our adaptive reuse plan represents a $2.5 million investment in the carbon-neutral-ready revitalization of a vacant bank building that once anchored a robust Main Street commercial and residential district that helped to bolster Central New York’s late-19th- and early-20th-century economy. Let’s work together to make that happen again.

We’re proud to be a part of Richfield Springs history—and look forward to being a part of our community’s future!